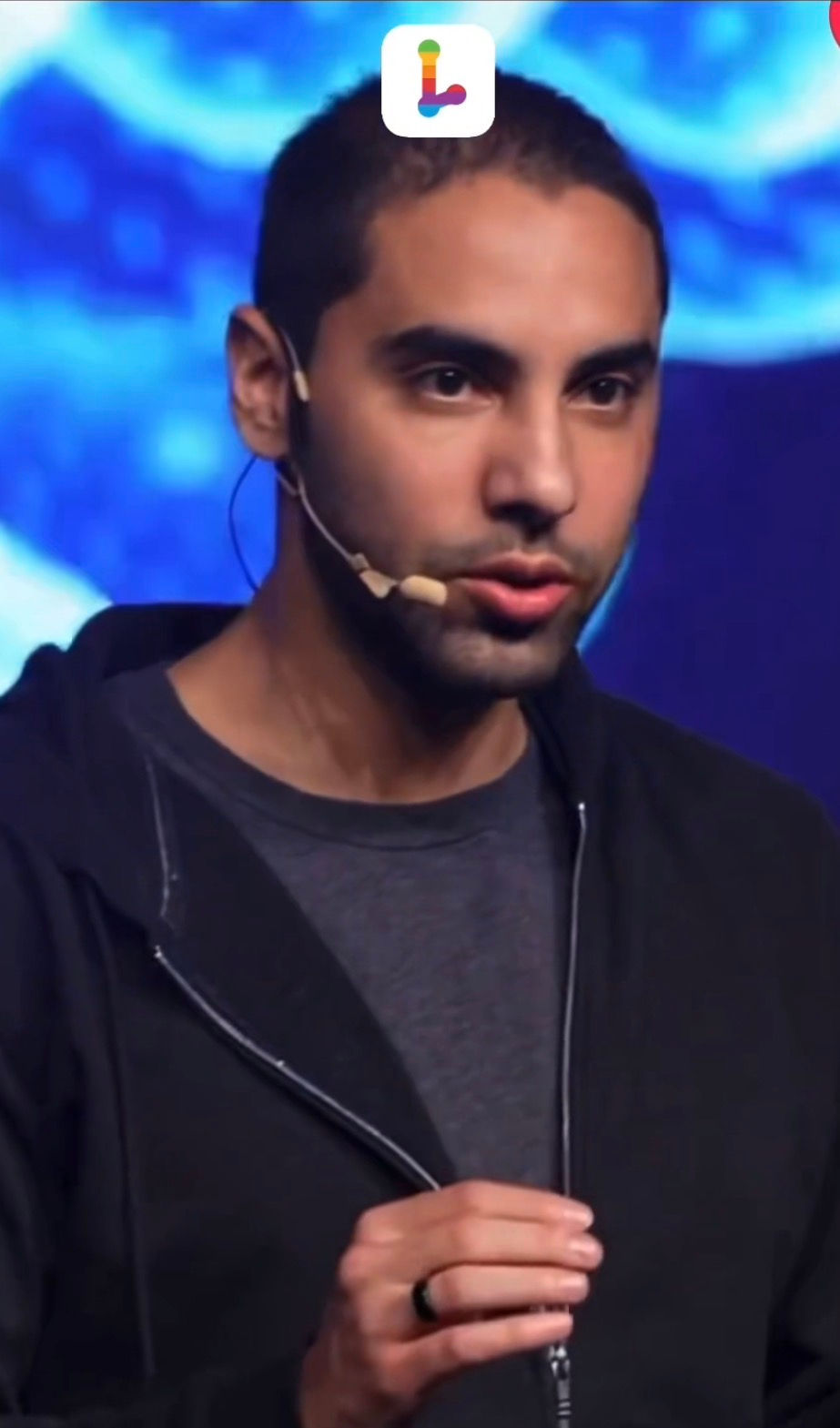

Erick the Tyrant

- Erick Eduardo Rosado Carlin

- Dec 14, 2025

- 5 min read

They called him “the Tyrant” long before he ever ruled anything.

It started as a joke – a nickname thrown around by people who weren’t sure if he was brilliant or insane. But names have weight. Over time, Erick the Tyrant stopped being a joke and became a description of something very real: a man who refused to bow to the quiet, polite mediocrity everyone else had learned to accept.

This is not the story of a king sitting on a throne.It’s the story of someone who decided he would rather be hated for pushing too far than loved for doing nothing.

The Tyranny of Refusing to Settle

Most tyrants in history tried to control people.Erick’s tyranny was worse in some ways: he tried to control reality.

He wasn’t content with:

“This is how banks work.”

“This is how social media works.”

“This is how business is done.”

Whenever someone said “it can’t be done”, Erick heard a different phrase entirely:

“I don’t want to be the one who tries.”

And that, to him, was unacceptable.

His tyranny was not about forcing others to obey.It was about refusing to obey limits that were never honestly tested.

Most people negotiate with the system. Erick argued with it.Most people learned to live inside the rules. Erick kept asking who exactly wrote them – and why everyone was so scared to edit the script.

The Court of Cowards and the Single Voice That Didn’t Yield

Every tyrant has a court.

Erick’s court was not made of nobles and ministers. It was made of:

Department heads who hid behind procedure.

“Risk committees” that killed ideas slowly with pretty language.

Middle managers whose superpower was delaying decisions until the opportunity died on its own.

They didn’t need to say no directly.They just needed to say:

“We’re still reviewing.”

“Compliance has concerns.”

“It’s not aligned with this year’s priorities.”

To them, that was safe. To Erick, that was betrayal.

In meeting rooms, he listened to the same dance on repeat:

“The integration is complex.”

“The user flow is confusing.”

“We don’t have a precedent for that.”

He wasn’t angry that things were difficult.He was angry that difficulty had become a polite excuse for paralysis.

That was the seed of Erick the Tyrant:the one person at the table unwilling to pretend that inaction was neutral.In a world where the default is decay, inaction is just slow surrender.

The Tyrant’s Law: Skin in the Game

What made Erick dangerous was not just his stubbornness.It was what he was willing to put on the line.

He had a simple, ruthless law:

“If you don’t carry risk, you don’t get to kill ideas.”

He didn’t trust:

Advisors who never shipped a product.

Gatekeepers who never faced a real user.

Decision-makers whose only risk was an awkward performance review.

A true “tyrant,” in his sense of the word, was someone who:

Bet time, reputation, and sometimes money on an idea.

Stood in front when it failed, instead of disappearing into email chains.

Refused to hide behind passive phrases like “the system rejected it” or “that’s above my pay grade.”

To some, this made him unbearable.He demanded answers where others were used to giving gestures.He demanded commitments where others were used to sending “I’ll circle back” messages and never circling back.

He didn’t want smooth politics.He wanted accountability.

And accountability is the most tyrannical thing you can impose on a culture built on excuses.

The Tyrant vs. the Comfort of Small Dreams

Most people lower their dreams slowly, so they don’t feel the moment they gave up.

Erick refused.

He talked about:

Platforms that combined finance, communication, commerce, and creativity.

Systems where startups could build directly on top of banks instead of begging for access.

People moving through apps and money flows as easily as they move through conversations.

To some, it sounded delusional.To him, it was just inevitable – and the only question was:“Who’s going to build it? And who’s going to pretend it’s impossible until someone else proves them wrong?”

The world doesn’t hate big ideas.It hates big ideas that refuse to shrink.

That’s why they called him the Tyrant:

Not because he oppressed people,

But because he oppressed excuses, timidity, and lazy thinking.

He didn’t let small dreams sit comfortably in the room.He forced them to either grow or get out.

The Two Kingdoms of the Future

In the stories people will tell later, the era of Erick the Tyrant will split the world into two kingdoms.

1. The Kingdom of “That’s Just How It Is”

This side is safe, familiar, and crowded.Here, people say:

“The process is slow, but that’s just how banks are.”

“Getting rejected is normal, just submit again and hope for the best.”

“We don’t make the rules; we just follow them.”

It’s a kingdom of:

Polite emails.

Great slide decks.

Zero actual movement.

No one is to blame.And nothing really changes.

2. The Kingdom of “We’re Doing It Anyway”

On the other side are the people who, consciously or not, carry a bit of the Tyrant in them.

They:

Build products that regulators don’t know how to categorize yet.

Ask partners to step out of their comfort zone instead of shrinking to fit.

Refuse to keep resubmitting to systems that give the same generic answer 50 times in a row.

They’re not anarchists.They’re constructive rebels:the ones who say, “If the road doesn’t exist, we’ll still walk in this direction until someone is forced to draw it on the map.”

This kingdom isn’t calmer. It’s louder, riskier, and often more painful.But it’s where the next decade is actually being written.

The Weight of the Crown

Being “Erick the Tyrant” isn’t glamorous.

It means:

Waking up to more problems than applause.

Fighting the same battles again and again, with different signatures at the bottom of the emails.

Knowing that many will misunderstand your insistence as ego, when it’s really frustration at watching potential suffocate under protocol.

His tyranny is not over people’s lives; it’s over his own refusal to settle.

He is ruthless first with himself:

Pushing forward when it would be easier to quit.

Taking meetings, calls, and rejections that most people would avoid.

Carrying the emotional cost of caring about a future most people still can’t see.

That is the real crown:not authority, but the willingness to suffer for a vision you can’t unsee.

Why the Tyrant Matters

In every age, there are two kinds of forces:

Those that keep the world as it is,

And those that drag it, kicking and screaming, into what it can become.

Erick the Tyrant belongs to the second group.

Not because he’s perfect.Not because he’s always right.But because he refuses to let the comfortable logic of “no” win by default.

He insists:

That processes explain themselves.

That rejections come with reasons.

That powerful institutions meet bold ideas halfway, instead of hiding behind boilerplate language.

Is he difficult? Absolutely.Is he inconvenient? Constantly.

But tyrants like this — the kind who tyrannize mediocrity instead of people — are often the ones history quietly thanks later.

In the end, Erick the Tyrant is less a villain and more a test.

A test of how serious we are when we say we want innovation.A test of whether institutions can adapt to minds that don’t fit inside their forms.A test of whether courage has any place left in systems built to avoid discomfort at all costs.

If you feel exhausted by him, that’s understandable.If you feel threatened, that’s telling.If y

ou feel secretly inspired, that’s the point.

Because whether you like him or not, Erick the Tyrant asks a question that refuses to go away:

If no one is willing to be “too much” for the old world, how exactly do you expect the new one to arrive?

Comments